by Doug Kreitzberg | Dec 28, 2020 | Business Continuity, Cybersecurity

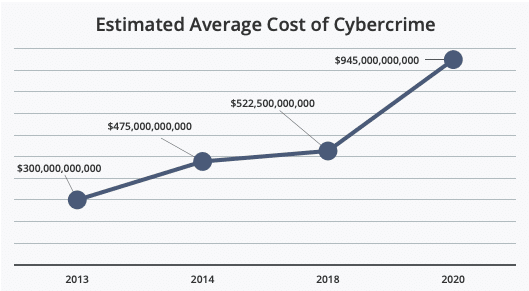

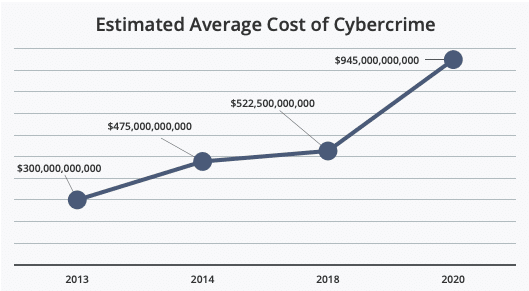

Earlier this year we wrote about the fact that cyber attacks cost businesses millions of dollars per incident. But what about the cost of cybercrime on larger scale? This month, McAfee released a new report analyzing at the cost of cybercrime globally, and the findings are staggering.

The most startling news from the report is the jump in the overall cost of cybercrime globally. Between 2018 and 2020, McAfee found a nearly 50% increase in average global cost. Now, the estimated global cost of cybercrime is $945 billion — more than 1% of the global GDP.

Source: McAfee

Just as startling, however, is that the report found a myriad of additional damages organizations face after a cyber incident beyond direct financial costs. In their report, McAfee found that 92% of organizations surveyed identified “hidden costs” that effected them beyond direct monetary losses. These hidden costs can have long terms effects on an organization’s productivity and ability to prevent future attacks.

One of the main hidden costs the report covers is the “damage to company performance” after a cyber incident. These damages, according to the report, is primarily related to a loss in productivity and lost work hours as businesses attempt to recover from an attack — usually because system downtime and disruptions to normal operations. While these losses might be, to some extent, inevitable following an attack, McAfee’s report found that organizations routinely neglect one essential aspect of cybersecurity: communication within the organizations.

We’ve talked before about the importance of creating an incident response plan, but without communication and cooperation between all areas of an organization, these plans won’t be all that effective. According to the report, IT decision makers think some departments aren’t ever made aware that a cyber incident even happened. The breakdown in communication is especially damaging between IT and business leadership. “IT and line-of-business (LOB) decision makers,” the report says, “have different understandings of what, why, and how a company or government agency is experiencing an IT security incident.” In fact, the lack of communication goes so far as whether or not there is even a response plan at all. The report found that, in general, business leadership often believe there is a response plan in place when there isn’t one.

This lack of communication also extends to the nature and scope of an organization’s cyber risk. The report noted a significant lack of organization-wide understand of cyber risk, which, the report states, “makes companies and agencies vulnerable to social engineering tactics. Once a user is hacked, they do not always recognize the problem in time to stop the spread of malware.”

While there will almost always be disruptions and hidden costs following a cyber incident, McAfee’s report seems to indicate many of these losses are self-inflicted. The report shows that the most common change organizations make after a cyber incident is investment in new security software. And, while technical safeguards are certainly necessary, they are far from sufficient. Instead, organizations need to begin investing in policies and procedures that ensure organization-wide communication, knowledge, and response to cyber risk and incidents.

by Doug Kreitzberg | Dec 23, 2020 | Business Continuity, Facebook, Privacy, small business

Ever since Apple announced new privacy features included in the release of OS 14, Facebook has waged a war against the company, arguing that these new features will adversely effect small businesses and their ability to advertise online. What makes these attacks so “laughable” is not just Facebook’s disingenuous posturing as the protector of small businesses, but that their campaign against Apple suggests privacy and business are fundamentally opposed to each other. This is just plain wrong. We’ve said it before and we’ll say is again: Privacy is good for business.

In June, Apple announced that their new mobile operating system, OS 14, would include a feature called “AppTrackingTransparency” that requires apps to seek permission from users before tracking activity between others apps and websites. This feature is a big step towards prioritizing user control of data and the right to privacy. However, in the months following Apple’s announcement, Facebook has waged a campaign against Apple and their new privacy feature. In a blog post earlier this month, Faceboook claims that “Apple’s policy will make it much harder for small businesses to reach their target audience, which will limit their growth and their ability to compete with big companies.”

And Facebook didn’t stop there. They even took out full-page ads in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Washington Post to make their point.

Given the fact that Facebook is currently being sued by more than 40 states for antitrust violations, there is some pretty heavy irony in the company’s stance as the protector of small business. Yet, this is only scratches the surface of what Facebook gets wrong in their attacks against Apple’s privacy features.

While targeted online adverting has been heralded as a more effective way for business to reach new audiences and start turning a profit, the groups that benefit the most from these highly-targeted ad practices are in reality gigantic data brokers. In response to Facebook’s attacks, Apple released a letter, saying that “the current data arms race primarily benefits big businesses with big data sets.”

The privacy advocacy non-profit, Electronic Frontier Foundation, reenforced Apple’s point and called Facebook’s claims “laughable.” Start ups and small business, used to be able to support themselves by running ads on their website or app. Now, however, nearly the entire online advertising ecosystem is controlled by companies like Facebook and Google, who not only distribute ads across platforms and services, but also collect, analyze and sell the data gained through these ads. Because these companies have a strangle hold on the market, they also rake in the majority of the profits. A study by The Association of National Advertisers found that publishers only get back between 30 and 40 cents of every dollar spent on ads. The rest, the EFF says, “goes to third-party data brokers [like Facebook and Google] who keep the lights on by exploiting your information, and not to small businesses trying to work within a broken system to reach their customers.”

Because tech giants such as Facebook have overwhelming control on online advertising practices, small businesses that want to run ads have no choice but to use highly-invasive targeting methods that end up benefitting Facebook more than these small businesses. Facebook’s claim that their crusade against Apple’s new privacy features is meant to help small businesses just simply doesn’t hold water. Instead, Facebook has a vested interest in maintaining the idea that privacy and business are fundamentally opposed to one another because that position suits their business model.

At the end of the day, the problem facing small business is not about privacy. The problem is the fundamental imbalance between a handful of gigantic tech companies and everyone else. The move by Apple to ensure all apps are playing by the same rules and protecting the privacy of their users is a good step towards leveling the playing field and thereby actually helping small business grow.

This also shows the potential benefits of a federal, baseline privacy regulation. Currently, U.S. privacy regulations are enacted and enforced on the state level, which, while a step in the right direction, can end up staggering business growth as organizations attempt to navigate various regulations with different levels of requirements. In fact, last year CEOs sent a letter to congress urging the government to put in place federal privacy regulations, saying that “as the regulatory landscape becomes increasingly fragmented and more complex, U.S. innovation and global competitiveness in the digital economy are threatened” and that “innovation thrives under clearly defined and consistently applied rules.”

Lastly, we recently wrote about how consumers are more willing to pay more for services that don’t collect excessive amounts of data on their users.This suggests that surveillance advertising and predatory tracking do not build customers, they build transactions. Apple’s new privacy features open up a space for business to use privacy-by-design principles in their advertising and services, providing a channel for those customers that place a value on their privacy.

Privacy is not bad for business, it’s only bad for business models like Facebook’s. By leveling the playing field and providing a space for new, privacy-minded business models to proliferate, we may start to see more organizations realize that privacy and business are actually quite compatible.

by Doug Kreitzberg | Dec 16, 2020 | Behavior, Cybersecurity, Privacy

In recent years, much has been made of the privacy paradox: the idea that, while people say they value their privacy, their online behaviors show they are more willing to give away personal information than they’d like to think. Tech giants like Facebook and Google have faced a number of highly public privacy standards, yet millions upon millions of users continue to use these services every day. However, what happens when we think of the value of privacy not in terms of how much we want to protect our privacy, but instead in terms of much we are willing to spend to keep our data private. Newly published research does just that and found that, when looking at the dollar value people place on privacy, there might not be as much as a paradox as we suspected, and business can even learn to leverage the market value of privacy to better understand what they should (and shouldn’t) collect from consumers.

The new study, conducted by assistant professor at the London School of Economic Huan Tang, analyzed how much personal information users in China were willing to disclose in exchange for consumer loans. Official credit scores do not exist in China, so consumers typically have to give over a significant amount of personal information in order for banks to assess their credit. By looking at the decisions of 320,000 users on a popular Chinese lending platform, Tang was able to compare user’s willingness to disclose certain pieces of sensitive information against the cost of borrowing.

The results? Tang found that users were willing to disclosure sensitive information in exchange for an average of $33 reduction in loan fees. While for many in the U.S., $33 may not seem all that significant, $33 actually represents 70% of the daily salary in China, showing users place a significantly high value on their privacy. What’s more, on the bank’s side this translates to 10% decrease in revenue when they require users to disclosure additional personal information.

There are a number of important implications of these study for businesses. For one, it suggests, as Tang says, “that maybe there is no ‘privacy paradox’ after all,” meaning consumers’ online behaviors do, in fact, seem to show a value on protecting people’s right to privacy. While today businesses often utilize the data they collect to make money, by collecting everything and anything they can get their hands on, businesses may be losing significant revenue in lost business. According to Tang, collecting more information than necessary turns out to be inefficient. Instead, business can leverage the monetary value users place on their data to be more discerning when deciding what information to collect. If a piece of data is highly valued by consumers and has little direct economic benefits for a company, it may not be worth collecting. Of course, limiting data is a key tenet of Privacy by Design principles, which organization should be applying to our their practices in order to improve their privacy posture vis-a-vis GDPR and other privacy regulations. Limiting data also improves the organization’s cybersecurity posture because it reduces its exposure.

While it may seem counter intuitive in today’s standard practice of collecting as much data as possible, this study shows that limiting the data that is collected can be, according to Tang, a “win-win” for businesses and consumers alike.

by Doug Kreitzberg | Dec 10, 2020 | Uncategorized

Every so often something comes along and disrupts the normal order of things, and out of that disruption a something new emerges. It’s certainly not a stretch to say that 2020 has brought plenty of disruptions with it, and according to a recent report by Gartner, businesses are starting “reset” how they operate and implement new strategies reliant on emerging, more sophisticated technologies. In the report, Gartner lists a number of predictions for what the future of business will look like. Perhaps the most startling prediction the report makes is the increase in workplace surveillance: “By 2025, 75% of conversations at work will be recorded and analyzed, enabling the discovery of added organizational value or risk.” Whether this prediction will turn out to be true is up for debate, however the tone of the report seems to imply there isn’t much we can do about it. The problem, of course, is that these changes don’t appear out of thin air. People create the change. This means, if Gartner’s prediction turns out to be true, we aren’t completely helpless and could even play a role in building new technologies based on the values and ethics people share. Just like there is a movement in cybersecurity to create technologies that are based on privacy by design, as we begin moving towards a new future, we also need to focus on creating technology based on an ethics by design that promotes the well-being and rights of individual

While the idea of having every conversation and interaction you have at work recorded and analyzed probably doesn’t sound to appealing to employees, Gartner’s report highlights the possible benefits this will have for businesses. As Magnus Revang, research vice president at Gartner, explained to Tech Republic, “By analyzing these communications, organizations could identify sources of innovation and coaching throughout a company.” This may certainly be true. In fact, organizations could even use this data to help improve the workplace for employees.

Of course, if we’ve learned anything in the past decade, the technology that is used for good can also be used for bad. And Revang recognizes the risk involved with this shift. “I definitely think there [are] companies that are going to use technology like this and misuse it, and step over the line of what you would call ethical or moral.” When used correctly, however, Revang belives the benefits of the this technology will outweigh any possible risks.

The problem with this argument, however, is that it assumes the problem is not with the technology itself, but the people who use it. According to Tech Republic, Revang believes “technology is inherently neutral, however the way an organization chooses to deploy and use a technology is another consideration.” What this way of thinking doesn’t consider, however, is that technology is built by people — people who are certainly far from neutral. As Joan Donovan, a social science researcher at Harvard University, recently put it, the technology we build encodes “a vision of society and the economy.”

Humans are flawed, and technology is stained with our flaws before it is even operationalized. So, when looking towards the future of technology in business, without designing these new innovations with an ethics in mind, our underlining biases and flaws will play a big role in the consequences this technology will have for our everyday lives. This has huge implications in every facet of society, and unfortunately, our ethical oversight structures are very weak to mitigate these threats.

There’s talk about privacy by design principles and there are AI-bias frameworks being developed. But, in order to create technologies that support our better angels and not our worse impulses, we need experts across all fields and sectors to work together in order to understand and develop ethics by design principles that can help build technologies that are not only useful, but that reflect the values and ideals for a more just and equitable society.

by Doug Kreitzberg | Dec 9, 2020 | Business Email Compromise, Data Breach, Disinformation, Human Factor, Phishing

Yesterday, I received an email from a business acquaintance that included an invoice. I knew this person and his business but did not recall him every doing anything for me that would necessitate a payment. I called him to about the email and he said that his account had been indeed hacked and those emails were not from him. What occurred was an example of business email compromise (BEC) using stolen credentials.

Typically, BEC is a form of cyber attack where attackers create fake emails that impersonate executives in order to convince employees to send money to a bank account controlled by the bad guys. According to the FBI, BEC is the costliest form of cyber attack, scamming business out of $1.7 billion in 2019 alone. One reason these attacks are becoming so successful is because attackers are upping their game: instead of creating fake email address that look like a CEO or a vendor, attackers are now learning to steal login info to make their scams that much more convincing.

By compromising credentials, BEC attackers have opened up multiple new avenues to carry out their attack and increase the change of success. Among all the ways compromised credentials can be used for BEC attacks, here are 3 that every business should know about.

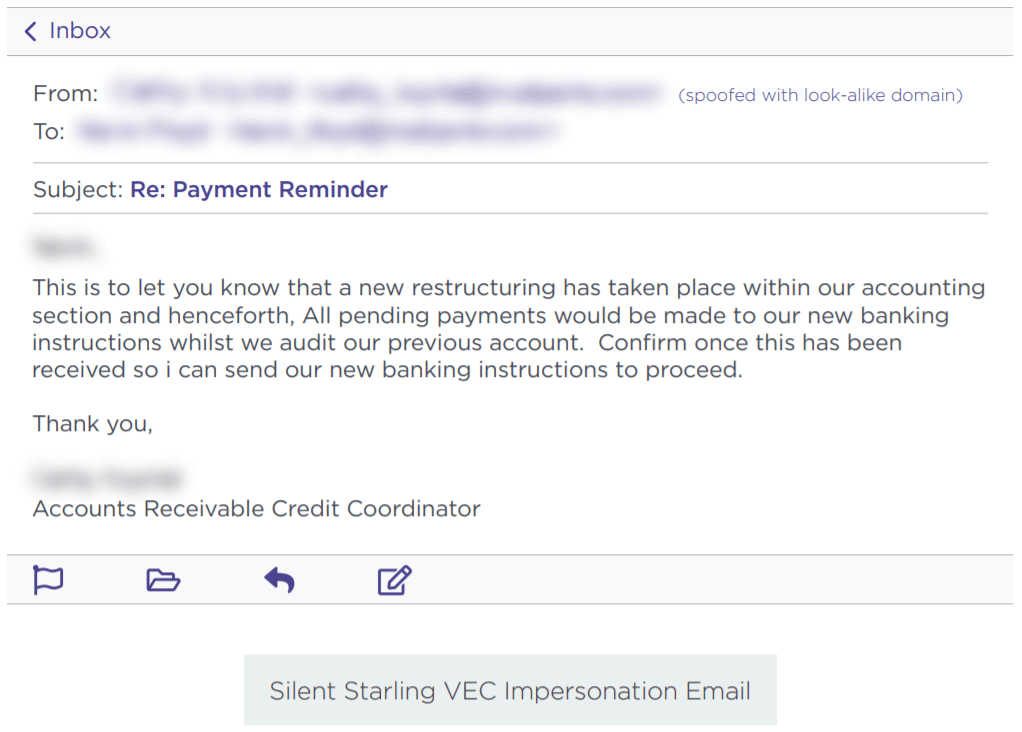

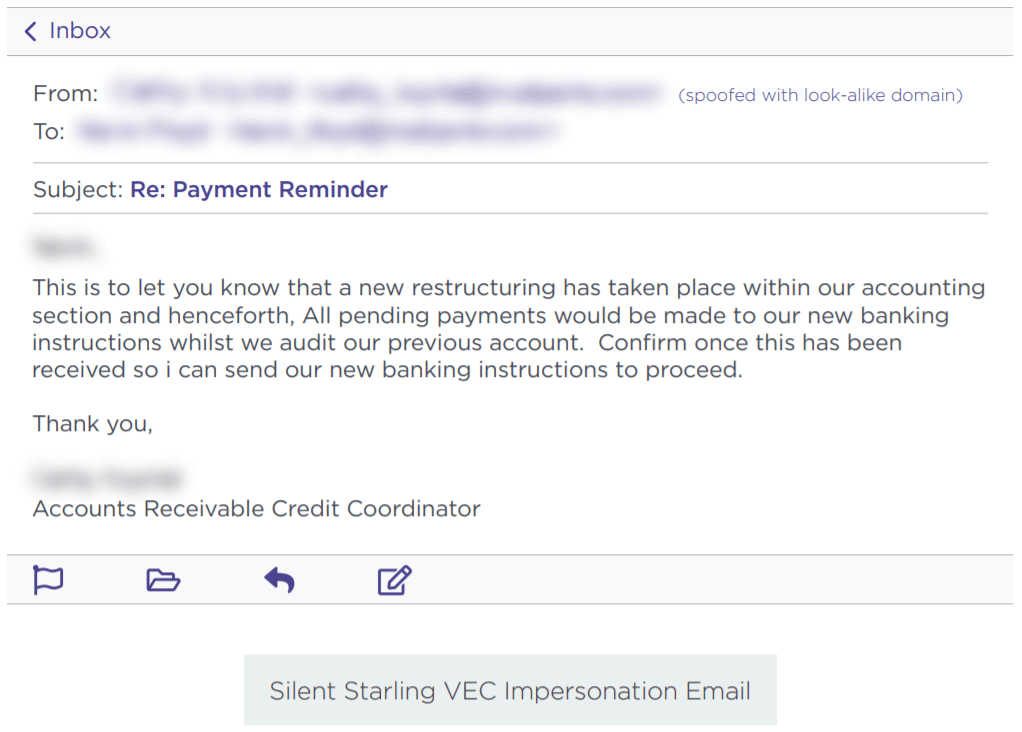

Vendor Email Compromise

One way BEC attackers can use compromised credentials has been called vendor email compromise. The name, however, is a little misleading, because vendors aren’t actually the target of the attack. Instead, they are the means to carry an attack out on a business. Essentially, BEC attackers will compromise the email credentials of an employee at the billing department of a vendor, then send invoices from that email to businesses requesting they make payment to a bank account controlled by the attackers.

Source: Agari

Inside Jobs

Another way attackers can use compromised credentials to carry out BEC scams is to use the credentials of someone in the finance or accounting department of an organizations to make payment requests to other employees and suppliers. By using the actual email of someone within the company, payments requests look far more legitimate and increase the change that the scam will succeed.

What’s more, attackers can use compromised credentials of someone in the billing department to even target customers for payment. Of course, if the customers make a payment, it goes to the attackers and not to the company they think they are paying. This is a new method of BEC, but one that is gaining steam. In a press release earlier this year, the FBI warned of the use of compromised credentials in BEC to target customers.

Advanced Intel Gathering

Another method to use compromised credentials for BEC doesn’t even involve using the compromised account to request payments. Instead, attackers will gain access to the email account of an employee in the finance department and simply gather information. With enough time, attackers can study who the business releases funds to, how often, and what the payment requests look like. With all of this information under their belt, attackers will then create a near-perfect impersonation of the entity requesting payment and send the request exactly when the business is expecting it.

Attackers have even figured out a way to retain access to employee’s emails after they’ve been locked out of the account. Once they’ve gained access to an employee’s inbox, attackers will often set the account to auto-forward any emails the employee receives to an account controlled by the attacker. That way, if the employee changes their password, the attacker can still view every message the employee receives.

What you can do

All three of these emerging attack methods attack should make businesses realize that BEC is a real and dangerous threat. It can be far harder to detect a BEC attack when the attackers are sending emails from a real address or using insider information from compromised credentials to expertly impersonate a vendor. Attackers can gain access to these credentials in a number of ways. First, through initial phishing attacks designed to capture employee credentials. Earlier this year, for example, attackers launched a spear phishing campaign to gather the credentials of finance executives‘ Microsoft 365 accounts in order to then carry out a BEC attack. Attackers can also pay for credentials on the dark web that were stolen in past data breaches. Even though these breaches often involve credentials of employees’ personal accounts, if an employee uses the same login info for every account, then attackers will have easy access to carry out their next BEC scam.

While the use of compromised credentials can make BEC harder to detect, there are a number of things organizations can do to protect themselves. First, businesses should ensure all employees—and vendors!—are properly trained in spotting and identifying phishing attacks. Second, organizations should require proper password management is for all users. Employees should use different credentials for every account, and multi-factor authentication should be enabled for vulnerable accounts such as email. Lastly, organization should disable or limit the auto-forwarding to prevent attackers from continuing to capture emails received by a targeted employee.

Businesses should also ensure employees in the finance department receive additional BEC training. A report earlier this year found an 87% increase in BEC attacks targeting employees in finance departments. Ensuring employees in the finance department know, for example, to confirm any changes to a vendor’s bank information before releasing funds, is key to protecting your organization from falling prey to the increasingly sophisticated BEC landscape.